Please welcome fellow Dreamspinner author Jamie Fessenden! Jamie is also a former musician, and although I haven’t quite convinced him that we should jam together, maybe one of these days…. Jamie’s new novel, Murderous Requiem, features a musician and has at its focus a mysterious piece of music.

Please welcome fellow Dreamspinner author Jamie Fessenden! Jamie is also a former musician, and although I haven’t quite convinced him that we should jam together, maybe one of these days…. Jamie’s new novel, Murderous Requiem, features a musician and has at its focus a mysterious piece of music.

Be sure to comment on Jamie’s post, since everyone who does will be entered to win a copy of the book! The contest ends at midnight on Sunday, July 7th. -Shira

******

I was once, a very long time ago, a music theory major. While I was working toward my degree, I had the opportunity to perform in a small choir specializing in music from the Renaissance, and to take a graduate-level course offered by my choir director in transcribing Renaissance musical notation into modern notation. My occult mystery novel, Murderous Requiem, owes much to that experience—not only for Jeremy’s expertise in Renaissance music, but also his interest in Marsilio Ficino and the occult influence of music on the human spirit. I stumbled across the latter doing a term paper for the course.

It might help to get some idea of what the music sounds like, before seeing what it looks like. This is the first complete mass whose composer can be identified—Messe de Nostre Dame (Mass of Our Lady), written by Guillaume de Machaut sometime before 1365:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11A4wqv8_wo

It’s about an hour, so you can chose to listen to the whole thing or not as you please. If you click on a point about halfway through, there’s a good example of four part harmony from the period. This mass is likely to have been known to Ficino, who lived from 1433 to 1499.

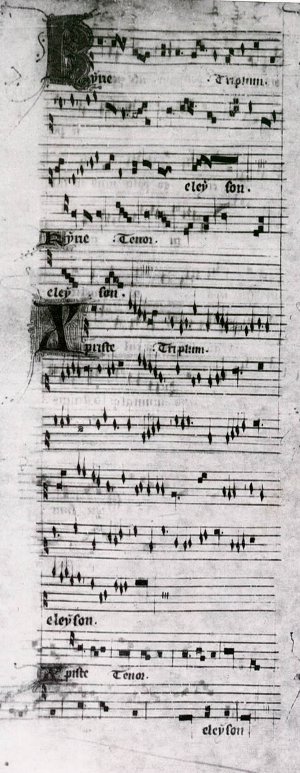

Unlike earlier religious music, which often sounds rather thin to our ears, this sounds more or less familiar. However, when we look at the notation, it ceases to resemble what we are familiar with today. You can see from the section of Machaut’s original manuscript below that a piece in four-part harmony was often laid out on the page with each voice in a separate section, as opposed to being lined up, one under the other. They also appeared to be different lengths, since there were no bar lines to denote measures and more attention was paid to making it all fit on the page than to visual alignment. The singers were expected to know their parts well enough for it to sync up during performance.

or less familiar. However, when we look at the notation, it ceases to resemble what we are familiar with today. You can see from the section of Machaut’s original manuscript below that a piece in four-part harmony was often laid out on the page with each voice in a separate section, as opposed to being lined up, one under the other. They also appeared to be different lengths, since there were no bar lines to denote measures and more attention was paid to making it all fit on the page than to visual alignment. The singers were expected to know their parts well enough for it to sync up during performance.

Aside from that, the notation itself looks very odd. Take for example the first few notes on that first line. The first represents a dotted whole note, and makes sense, if you ignore the fact that it’s filled in. But what about that odd zig-zag note directly following it? That’s how Machaut indicated three half notes followed by a whole note.

It becomes even more complicated, when we realize that the lack of bar lines to denote measures also meant that there were no ties. And the duration of a note was often indicated by writing a longer note, followed by a note whose value the singer was expected to subtract from the first note to reach the correct value!

If you have a burning desire to delve into this subject further (Come on! You know you do!), there is a huge amount of information on this site: http://anaigeon.free.fr/e_mensur_intro.html

So Jeremy has his work cut out for him in Murderous Requiem. In reality, it would probably take longer than a week for him to sort it all out. But I’ll just claim “poetic license” on that.

I am giving away a free copy of Murderous Requiem in eBook or autographed paperback—whichever you choose—to one person who comments on this blog before midnight on July 7th!

******

Blurb:

Jeremy Spencer never imagined the occult order he and his boyfriend, Bowyn, started as a joke in college would become an international organization with hundreds of followers. Now a professor with expertise in Renaissance music, Jeremy finds himself drawn back into the world of free love and ceremonial magick he’d left behind, and the old jealousies and hurt that separated him from Bowyn eight years ago seem almost insignificant.

Then Jeremy begins to wonder if the centuries-old score he’s been asked to transcribe hides something sinister. With each stanza, local birds flock to the old mansion, a mysterious fog descends upon the grounds, and bats swarm the temple dome. During a séance, the group receives a cryptic warning from the spirit realm. And as the music’s performance draws nearer, Jeremy realizes it may hold the key to incredible power—power somebody is willing to kill for.

******

Excerpt:

Seth led us up to the attic, where there were more bedrooms, smaller rooms converted from the old Victorian servants’ quarters. There was also a room which was locked—an oddity in the Temple. Seth, of course, had no keys on him, but Bowyn had a key of his own. At a nod from the older man, Bowyn unlocked the door.

Then we stepped into an airlock. I’d never seen one in real life, but I’d seen them in movies. It was a small triangular space, a bit cramped for four people, with another metal door on the largest wall leading into the room. This wall also had climate controls with displays for the temperature and humidity of the room beyond. Bowyn produced an electronic key card from his pocket and swept it in front of a card reader. The inner door unlatched and he pushed it open.

The room we entered was a library. A beautiful old Victorian library with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves on every wall and ladders on runners to provide access. The furniture in the room consisted of antique stuffed chairs and mahogany tables with Tiffany lamps casting a soft light to read by. In one corner, there was a large antique globe. There was even a fireplace, though I could see at a glance that it was electric and probably put out no heat in the climate-controlled environment.

“Didn’t this used to be a spare bedroom?” I asked as I wandered into the room.

Bowyn answered, “It used to be three spare bedrooms.”

“Now,” Seth said, “it’s the Order’s occult library.” He began circling the room, gesturing as he spoke. “All first editions, collected from all over the world—Crowley… Fortune… Levy… Dee… Mathers… Regardie… Waite…. The original works, in their first incarnations. You won’t find any reprints here. No cheap mass-produced paperbacks.” He said the word “paperbacks” as if it were a revolting concept to him.

“All under lock and key?”

“Every fifth- and sixth-level initiate has a key,” Seth replied. There were only seven levels in the Order, the Brethren being the seventh and highest. “All the others can access the entire library on an internal database, but only high-level initiates can come up here and actually touch the books; read them first-hand.”

Knowing Seth’s fascination with antiques and history, I wasn’t surprised it was so important to him to hold a first edition of The Book of Lies in his hands. It seemed a bit extravagant, especially if it was being paid for out of Temple funds—which I suspected it was, at least in part. But as long as it was approved by the others in the Order, I supposed I had no quarrel with it. I had to remind myself it wasn’t really my concern, in any case. I’d left the Order.

Seth moved to the far wall, where there were a number of wide, recessed drawers. “This, however, is the pride of our collection.”

I moved closer as he slid one of the drawers out. It contained several pages of what might have been a single document—quite an old document, judging by the yellowing of the parchment and the faded ink—secured in position under a large plate of Plexiglas. “We’ve collected some of the oldest occult texts still in existence. Fragments of medieval grimoires; pages from works by Agrippa, Fludd, Paracelsus, Weyer, Borrichius….”

He flipped a switch on the side of the drawer and long black lights on the inner sides of the drawer came on, causing the faded ink on the manuscripts to luminesce. “And here, my prodigal son, is what you’ve come home for.”

I ignored the annoying reference, my full attention caught by the beautifully shimmering staves of music now visible on the pages. I stepped closer, dismayed to see the poor condition of many of the pages. The edges were frayed and crumbling, and fingerprints—perhaps not noticeable when they were made, but now etched into the parchment—obscured some of the writing. A small stain of some unknown liquid smeared the ink in the upper corner of one page. In many places, I would have to make an educated guess as to which notes were meant.

But it was beautiful.

21 comments